I am the Director of The Salvation Army International Heritage Centre which holds the archives, reference library and other heritage items relating to this international church and charity. As well as caring for these collections and providing access to them, my colleagues and I also research aspects of Salvation Army history. The existence of a Salvation Navy in the 1880s isn’t well known, even within our own history, and it’s a story that I’ve been keen to highlight for some time.

This year, 2024, is the 150th anniversary of the Salvation Army opening its first chapel in Wales. Part of the celebrations of this has been to find stories from our work in Wales over the years. So I decided to look in more detail at the Salvation Navy, whose ships were given by a Cardiff industrialist and which we knew held evangelical meetings in Cardiff dock.

The Heritage Centre holds a small archive of original documents and photographs relating to the Salvation Navy, as well as supporting information in contemporary Salvation Army periodicals, primarily the weekly newspaper, The War Cry. I was surprised, therefore, to discover how little anyone know about the actual history and detail of the Salvation Navy. The official History of The Salvation Army only includes the most basic details and our own catalogue records included little more detail, for instance we knew nothing about the later years of the Salvation Navy and had no date for when it was wound up. I supplemented our records with contemporary newspaper reports from the British Newspaper Archive and have been able, for the first time, to piece together the story of The Salvation Navy.

That story begins in August 1885 when the first flagship of The Salvation Navy was launched. The SS Iole’s three masts flew the Salvation Army colours of red, blue and yellow, alongside flags bearing the words ‘Are you Saved’ and ‘Holiness unto the Lord’. Her sails carried the monogram ‘SN’ for Salvation Navy. The Iole was described by her first commander as looking ‘like a bird on the water.’ (‘Description’ 4)

The Salvation Army had been founded by William and Catherine Booth in 1865. In 1884, the Booths were offered the Iole, a 100ft steam yacht, by one of their wealthier supporters- John Cory, a coal broker and ship-owner from Cardiff, who had originally bought the yacht for his wife. It was described as ‘a little gem, perfect in all her appointments, which are, indeed, almost too luxurious for salvationists.’ in the Salvation Army’s magazine All the World (‘S. S. Iole’ 19)

The crew of the SS Iole was assembled from Officers (ministers) and Soldiers (members) of the Salvation Army with nautical backgrounds. Command of the Iole was given to ‘ex-Admiral’ Sherrington Foster who had been master of the Hartlepool lifeboat. The purpose of the Salvation Navy was “to visit every fishing town and seaport village along the English, Irish, Scotch and Welsh coast, boarding every vessel when lying in any roadstead, giving Bibles and good books, preaching Christ, and doing all in our power to get the sailors and fishermen of our country converted.” The Salvation Army’s newspaper, The War Cry, dramatically stated that the Iole had been ‘chartered by the King of Kings to go on a fishing expedition for men’ (‘Our Navy’ 13)

While attempts to secure a second ship for the Salvation Navy were unsuccessful, ‘Naval Brigades’ were established in the communities it worked amongst. Ships whose captains and crews were made up of Salvationists were encouraged to fly the Salvation Army colours and to ‘labour specially for the salvation of their fellows of the deep’ (‘The Salvation Navy’ 159). A pamphlet of Salvation Navy Songs was published for use by the Brigades.

In the summer of 1886 the Iole was visiting East Anglian ports when disaster struck as the Iole was sailing for Hull. On the evening of 11 June 1886, she struck a sandbank in the Humber and the crew had to row ashore in the lifeboat. It was reported that, the next morning, ‘at dead low water only two or three feet of the Iole’s funnel was to be seen’ (‘General Booth’s Yacht’ 2).

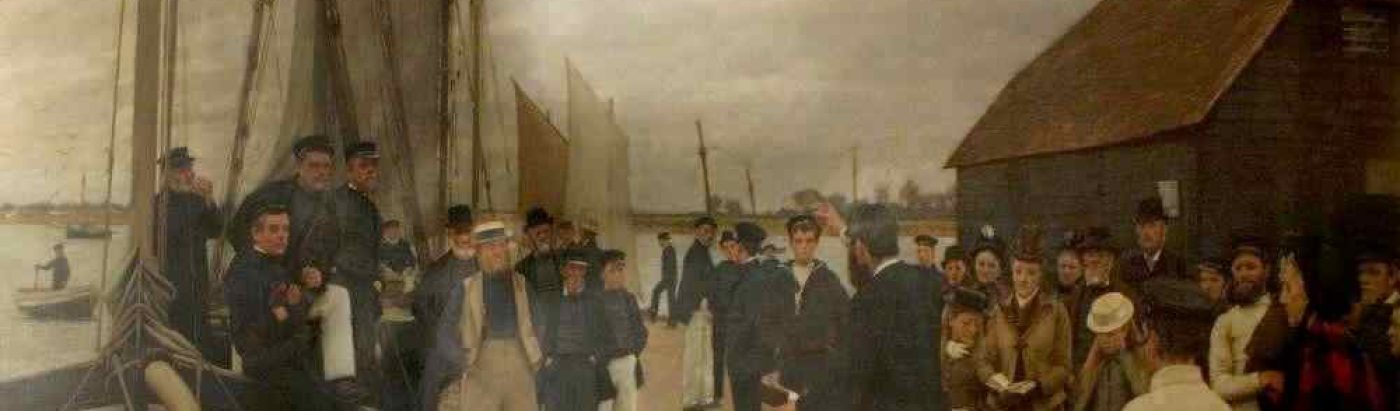

The Salvation Navy was without a ship for some seven months until John Cory again came to the rescue and gave an 82 foot racing yacht, the Vestal, to Booth. This became known as the ‘Salvation Gun-Boat’. Although the Vestal was ‘awaiting orders’ in a Southampton shipyard in February 1887, she had to await significant repairs before she could be launched on 5 April (‘Yachting’ 7. Her first captain was Abbot Taylor, previously the ‘skipper of a Brixham smack’ (The Salvation Navy Yacht 3). The Vestal continued the evangelical work that had been carried out by the Iole, visiting Bridport and Watchet in July and carrying out an evangelical campaign along the south Wales coast in the winter, spending Christmas 1887 in Cardiff Dock.

While the Salvation Navy may only have been short-lived, it shows General Booth and the Salvation Army learning from and developing the missions to mariners that had been active since early in the century. The militaristic language and embellished metaphors illustrate the dynamic innovations of The Salvation Army in the 1880s.

By Steven Spencer, Salvation Army International Heritage Centre

Sources

- ‘Description of our Salvation Stream Yacht ‘Iole.’ Rough report by Staff-Captain Foster’, The War Cry, 17 June, p. 4.

- ‘General Booth’s Yacht Sunk in the Humber,’ Norwich Mercury, 16 June, p. 2.

Booth, William. 1886. Orders and Regulations for Field Officers of The Salvation Army (International Headquarters of The Salvation Army), p. 569.

- ‘The Salvation Navy,’ The Salvation War, p. 159.

- ‘The Salvation Navy Yacht Vestal,’ Western Daily Press, 17 September, p. 3.

- ‘S. S. Iole,’All the World, January, p. 19.

- ‘Our Navy,’ The War Cry, 6 March, p. 13.

- ‘Wanted for the Salvation Yacht Vestal,’ The War Cry, 19 May, p. 7.

- ‘Yachting,’ The Hampshire Independent, 26 February, p. 7.