It was exciting to present new research on the religious beliefs and practices of British sailors to the Ecclesiastical History Society conference, held in Edinburgh this week from 15-17 July 2025.

The theme for this year’s EHS conference was Creeds, Councils and Canons in recognition of the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea, held in 325 AD. Presenters chose to address the theme across the full span of Christian history, and was vigorously debated by historians of the early Christian world, and all later periods up to the present.

For my paper, I wanted to tackle one of the more challenging issues facing the Mariners project team – namely, what did sailors believe about religion? We know quite a bit about what other people, including missionaries, shipping companies and the state wanted them to believe, and the various ways they sought to improve their living and working conditions and moral standing, but what the sailors felt about these interventions is a much harder nut to crack.

My research looked at the image of ‘Jack Tar’ as a careless and largely irreligious simpleton, with far too much interest in drink, sex and violence. Writers of popular songs and caricatures, such as Dibdin and Rowlandson, wrote stongs with titles such as ‘The Sailor’s Prayer’ and ‘The Sailor’s Creed’ which assumed sailors had no religion or moral scruples other than looking out for their shipmates and hoping for a good captain, a rich prize, and fair weather.

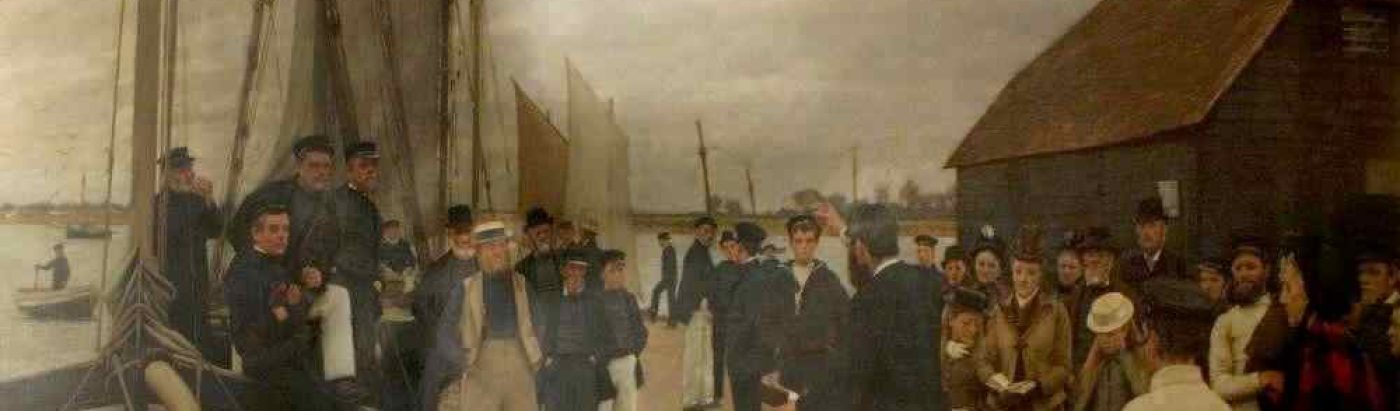

Yet missions to seamen sought to elevate the poor sailor, provide them with greater dignity and self-worth, and abandon their wanton ways. In their attempts to reach this body of men, marine missionary societies adopted a flexible strategy which minimised doctrinal differences, and promoted a simple message couched in salty language.

There were some variations. The Anglican agencies such as the Missions to seamen generally stressed that they were providing a national service regardless of other divisions. Dissenters who supported the Non-denominational movement, such as the British and Foreign Bible Society, followed the model of the London Missionary Society, affirming that they promoted a pure Christianity without concern for class or creed. This was illustrated by missionary promotional images, such as the BFBS ‘Gospel Ship’.

Having presented my paper in the first session of the conference, this left me free to enjoy other speakers. EHS President Sara Parvis provided the essential grounding for the conference theme with a rich account of the canons of the Nicene Creed and their reception. Other highlights for me was the paper by Gemma King on teaching the Church of Scotalnd’s Shorter Catechism in religious fiction; Angela Berlis on the Old Catholics resistance to the First Vatican Council, and Ivan Broisson on the great Etienne Gilson and his influence on the Second Vatican Council.

I followed several panels on missionary and ecumenical gatherings in Africa and India. Brian Stanley outlined the challenges of the attempt to integrate the International Missionary Council and the World Council of Churches at the Ghana Assembly of the IMC in 1957-8. the My fellow Australian, Nicole Starling, was enlightening on the conflict between deaconesses and high church sisterhoods in the diocese of Sydney. I was privileged to chair two fine papers on African missions by Alison Zilversmit on the Southern Rhodesia Missionary Conference, and Deborah Gaitskell on Ecumenism in 1940s South Africa.

The weather was gloriously warm for Edinburgh; the company and the conversations rich and enjoyable. There was a warm reception to my new work on sailors’ religious mentality and it was profitable to be able to present with so many other scholars working at the cutting edge of religious history today.