I have just got back from a trip to the Black Country Living Museum in Dudley for the 2025 Social History Society annual conference.

It was my first visit to the living history museum, and found it very hard to tear myself away from the recreated worlds of the Victorian, Edwardian and – most recently – post-WWII eras to get back to the conference. I wandered in and out of the cottages showcasing the work of women chain makers, the noisescape of the machine press, and the canal with its retinue of coal barges and attendant ducks. There was a strong evocation of the industrial scene (though of course without the squalor, smoke and smells) and I was particularly impressed with the abandoned anchor, a remnant of the anchor makers who used to work in this area. In its own building was a recreation of the mighty Newcomen engine which, having once lived in a street (in Newcastle NSW) named after the great engineer, I found particularly impressive.

The conference was a packed schedule with up to five parallel streams around these broad themes, each curated by experts in their field.

- Bodies, Sex and Emotions

- ‘Deviance’, Inclusion and Exclusion

- Difference, Minoritization and ‘Othering’

- Heritage, Environment, Spaces & Places

- Inequalities, Activism and Social Justice

- Life Cycles, Families and Communities

- Politics, Policy and Citizenship

- Work, Leisure and Consumption

I enjoyed catching up with Emily Cuming, who gave a splendid paper on ‘sailor’s daughters’ which analyzed working class women’s memoirs of absent, and sometimes abusive, sailor fathers. Other highlights were presentations by four curators from different ‘living history’ museums: Simon Briercliffe, director of the Black Country Museum, Kate Hill, from the Cregneash Isle of Man Folk Museum , Natasha Anson, on the Beamish North East England museum, and educationish Megan Schlanker on the use of living history in schools. While we spoke, the Dudley museum was full of teams of school children so it was clear new learning memories were being laid down in these places. The curators pushed back robustly on calls to avoid nostalgia, or to answer calls to highlight or ignore particular aspects of the past. I was also very happy to listen to papers by Bristol colleagues, Marianna Dudley (on the history of wind turbines), and Will Pooley (on queer magic in 19th century rural France).

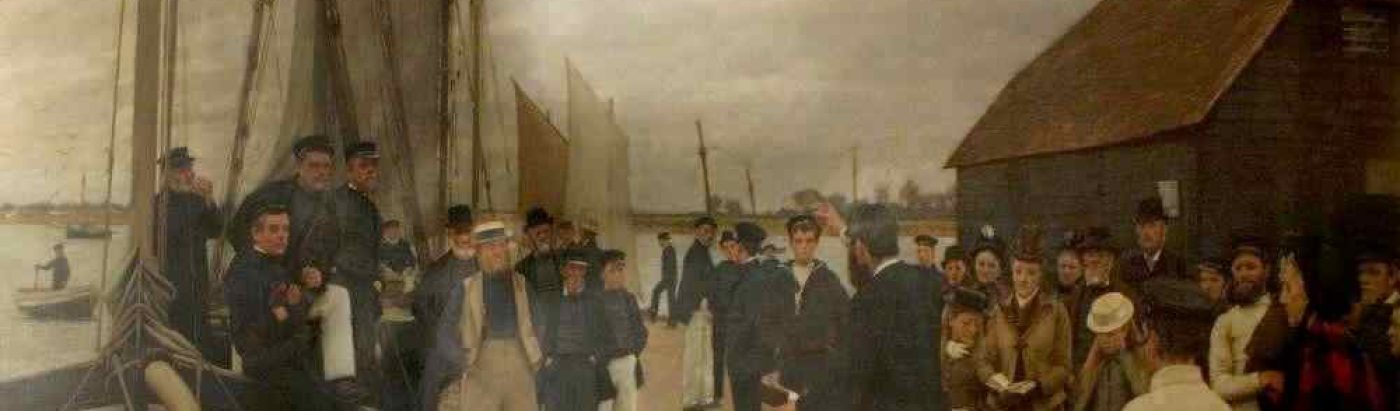

As part of the ‘inequalities, activism and social justice’ theme, my paper was in the last session of the last day, and I was grateful to those who stayed the course. It was a privilege to talk about the Mariners project to this engaged and active group of researchers. My topic was ‘Missions to Mariners’, and I spoke about the challenge for reformers of pushing back against the old stereotype of ‘Jack Tar’ in order to promote the value of the pious sailor. There is a wealth of printed and archival sources relating to the movement, much of which we have been exploring for this project, but it is much more difficult to understand the values of working sailors themselves. This is part of my conclusion:

The maritime mission movement would leave a visible mark on British port landscapes, with its floating chapels, on shore seamen’s churches, institutes and bethels, and provision for education, housing and other forms of welfare. Although very little of this religious infrastructure remains, it initiated a revolution in the image of the sailor, from ‘Jack Tar’ to sober worker, which by the end of the century had largely displaced the drunken caricature of an earlier era.

My paper will be included in the Special Issue of the Social History Society journal, Cultural and Social History. The revised papers from the Mariners conference held on the ss Great Britain are now coming in and we hope the whole collection will soon be available, online and fully open access.