The London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) specialises in the history of London and maintains records related to the development of London’s urban spaces and communities. I went there to consult documents on the seamen’s mission circuit and the Sailors’ Orphan Girls Home in Hampstead. While the Hull History Centre has most of the Hampstead home’s records, the LMA had some scattered documents on the institution and London’s seamen’s missions.

The LMA is housed in a brutalist building looking over a park. The reading room and reference centre floor had an exceptionally well-curated free exhibition on London’s racial minorities. I read several logbooks of the Wesleyan Chapel Trust seamen’s mission circuit (N/M/42/70) that described the frequency of preaching among seamen in five London locations: Brunswick Chapel (1832-), Mitre Buildings Sunday School (1843-), Queen Victoria Seamen’s Rest (1900-), Barking Road Chapel in Canning Town (1861-68), Barking Road Minister’s House (1894-) and Every Seamen’s Rest (1909). The local preachers also kept detailed minutes on the content of their lectures (N/M/42/69).

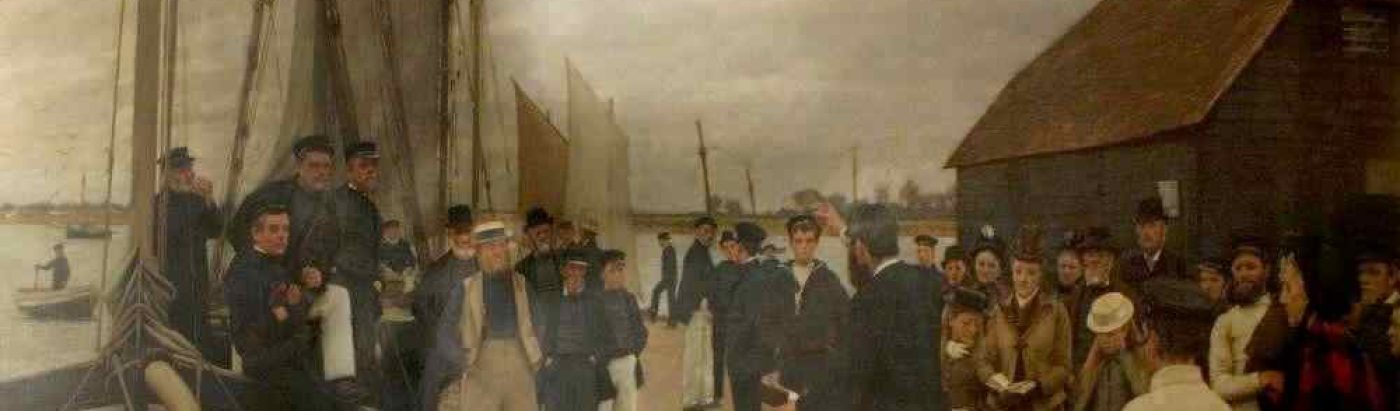

The archives held a large number of annual and occasional reports of the Sailors’ Orphan Girls School 9A/FWA/C/D/122/001) that provided an overview of the church’s work with orphans. Captain R.J. Elliott started the Home in Whitechapel in 1829 as a means to provide education to orphans of seamen and fishermen. The committee moved the institution to Frognal House in Hampstead in 1855, where they provided board, clothing, education, and training in domestic duties. It received children between the ages of five and 12, who remained there till 16. The Duke of Edinburgh led a fundraising campaign that helped the establishment of a new building in 1866.

The church and the admiralty jointly managed the enrolment and the religious and practical education of the orphans. Training in housework included cooking, laundry, and needlework, and the Home found them suitable jobs as they turned 16. The girls were given an outfit as they ventured out into the world, and prizes for serving for a long time at one place. The Home prided itself in saving orphaned children from poverty and ignominy, but its vision for preparing these children for life was grounded in archaic notions of class and gender roles: that working-class women could not aspire to become any more than servants. I will revisit Hull to consult other documents of the Home and generate a deeper understanding of the church’s role in orphan welfare.