We are delighted to be able to feature this fascinating piece from Bristol PhD student, Ting Ruan. Ting will be participating in the Mariners conference, coming up on 12-13 September 2024.

Ting writes:

I am a third-year PhD student in the History Department, and my research focuses on China’s coastal lighting construction during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This project involved the dissemination and adaptation of technology and, more broadly, embodied the presence of Britain’s informal empire and the globalisation process of that era.

China has a long coastline, stretching from its northeastern corner down to its southernmost point, but in the middle of the nineteenth century, it was largely unlit. The lighting was sporadic, and the facilities were primitive, using vegetable oil in lanterns made of oyster shells, which produced only a dull and smoky flame. Consequently, the lack of modern lighting became a major obstacle for foreign vessels approaching China’s waters. Merchants and captains cried out in the press about the losses in property and human lives caused by shipwrecks.

However, at that time, the Chinese Imperial Court was beset by both internal and external difficulties. Internally, it was plagued by the Taiping Rebellion, which lasted more than ten years and proved to be the largest peasant uprising in Chinese history. . Externally, it contended with European powers, striving to avoid the fate of complete colonisation like some Asian and African countries. Consequently, the Court lacked the resources to systematically build maritime facilities and did not possess the necessary technical personnel.

At the same time, a pivotal institution in China’s modern era was founded: the Chinese Maritime Customs Service. This institution had a unique characteristic: although it was always a branch of the Chinese government, from its establishment in 1861 until the Communist Party seized power in 1949, all six chief leaders were foreigners. Five were British (until 1943), and the last was an American. Its employees, however, came from as many as 23 countries around the world. Therefore, the Customs Service was a Chinese authority with a distinctly global dimension but was clearly dominated by Britain.

Another crucial feature of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service is that it went far beyond being a revenue-collecting agency. It was actively involved in a wide range of affairs in China, including diplomacy, military, postal services, meteorology, and education. Notably, it played a significant role in establishing China’s maritime infrastructure. Sir Robert Hart, the second and longest-serving head, was instrumental in making this ambitious project a success.

First and foremost was the issue of funding, which was the basis for everything. In 1868, Hart succeeded in securing 70 percent of the tonnage dues for the lighting project, a sum that the Customs retained exclusively for the construction and maintenance of lighthouses.

For the equipment, Hart, with the support of his loyal assistant James Duncan Campbell, the head of the Customs’ London Office, imported devices and components from Europe and the United States. The second half of the nineteenth century was a critical period in the evolution of lighthouse technology. The rapid development of steamship transportation and the consequent expansion of sea lanes created an increased demand for lighthouses. At the time, France was the world leader in lighthouse technology, with the invention of the Fresnel lens marking a significant breakthrough in the field. Additionally, Chance Brothers, a British company based near Birmingham that initially started as a glass manufacturer, gradually became a competitive producer of illuminating apparatus—specifically, the core component for lighthouses, the lighting device.. The Customs Service introduced sophisticated technologies, ensuring that China’s lighthouses were on par with the world’s advanced standards. By the 1920s, China’s coastline was praised as ‘one of the best lit coasts in the world’ (North China Herald, 11 February 1928). Looking back to the mid-nineteenth century, when foreign merchants and captains heavily complained about China’s lack of marine facilities, this accomplishment cannot be overstated.

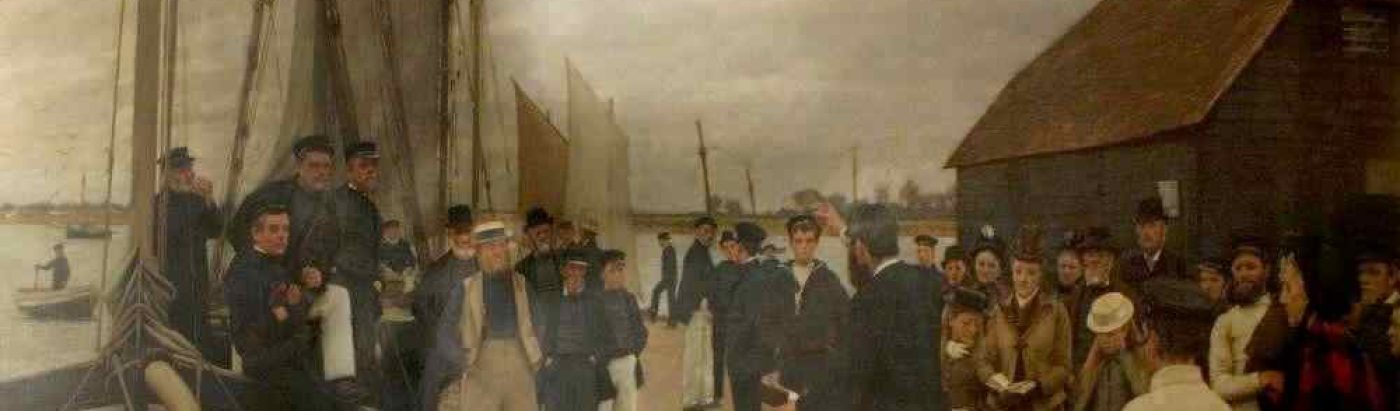

Source: Image courtesy of Special Collections, University of Bristol Library (www.hpcbristol.net).

Having advanced equipment was not enough; technical personnel were essential to design the lighthouses and adapt the technologies. This is where engineers were needed. One of the prominent figures in China’s lighthouse construction was an Englishman named David Marr Henderson. He was the Customs’ first engineer-in-chief, serving nearly 30 years in China. Almost all large coastal lighthouses were built under his supervision. He designed and supervised the construction of the greatest number of lighthouses in the world among his contemporaries. Henderson returned to England in 1898 and lived the rest of his life at Hove, East Sussex.. After his departure, the subsequent engineers-in-chief employed by the Customs were all Britons like him; it was not until the end of World War II that the position was held by Chinese engineers.

The engineers’ role was in designing and supervising the construction of lighthouses. Once a lighthouse was established, it was the lighthouse keepers who were responsible for its daily operation, ensuring that the light stayed on after sunset and that passing vessels navigated safely. Unlike the engineers, Chinese personnel were involved in the position of lighthouse keepers from an early stage. However, despite Chinese lightkeepers far outnumbering their foreign counterparts, they were largely limited to roles as assistants. Some of them were classed as ‘coolies’, who were not involved in work related to the light but were only assigned chores such as cleaning the house and painting the walls. The Customs was reluctant to appoint Chinese as lightkeepers-in-charge, particularly for large coastal lighthouses, until the 1920s. During this period, nationalist sentiment in China surged, forcing the Customs to adjust its personnel policies by restricting the proportion of foreign staff and promoting Chinese personnel to higher positions; only then were China’s lighthouses gradually placed under Chinese control.

However, until the outbreak of the Pacific War, a considerable number of large coastal lighthouses were still operated by foreigners. After 1949, when the Communist regime seized power, the history of foreign-controlled Customs came to an end. With only a few exceptions, Westerners were declared unwelcome in this country and driven away. China entered a whole new era. However, the lighthouses still stand along the coastline, guiding passing vessels. With the widespread use of GPS technology, lighthouses in China, as in the rest of the world, gradually lost their practical significance and became more of a tourist attraction. Their unique architectural style, integrated into the vastness of the ocean, soon became a popular holiday landscape, fascinating travellers from all over the world.

Nevertheless, their history always reminds us of the unique period that China went through and the legacy left even beyond its formal reach by the British Empire. These lighthouses embody the British imperial networks, which facilitated the transfer of technology, the movement of people and commodities, and the integration of different parts of the world into an ever-accelerating interconnected globe.

References:

- ‘The Lights of the China Coast’, North China Herald, 11 February, p. 239.

Banister, T. Roger. 1932. The Coastwise Lights of China: An Illustrated Account of the Chinese Maritime Customs Light Service (Shanghai: Statistical Department of the Inspectorate General of Chinese Customs)

Wright, Stanley F. 1952. Hart and the Chinese Customs (Belfast: Wm Mullan)

China. Maritime Customs. Reports on Lights, Buoys, and Beacons, 1875–1947 (Shanghai: Statistical Department of the Inspectorate General of Customs)

Chen, Xiafei and Han Rongfang (eds). 1990–1993. Archives of China’s Imperial Maritime Customs: Confidential Correspondence Between Robert Hart and James Duncan Campbell, 1874–1907 (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press)

Resources:

Chance, Toby and Peter Williams. 2008. Lighthouses: The Race to Illuminate the World (London: New Holland Publishers)

Levitt, Theresa. 2013. A Short, Bright Flash: Augustin Fresnel and the Birth of the Modern Lighthouse (New York: W. W. Norton & Company)

Van de Ven, Hans. 2014. Breaking with the Past: The Maritime Customs Service and the Global Origins of Modernity in China (New York: Columbia University Press).