I very much enjoyed getting down by the River Avon to explore Bristol Archives, which is part of Bristol Museums.

The Archives are a welcoming place, housed in B Bond Warehouse hard by the River Avon and the impressive engineering works that created the Floating Harbour. I was there to explore the one surviving Book of Minutes, 1843-1844, for the Bristol Channel Mission Society (BCMS), a forerunner of the Anglican Mission to Seafarers.

The BCMS originated in the efforts of the Rev. John Ashley to visit isolated maritime communities in the Channel, as well as the much larger number of ships moored in the Channel’s roadsteads waiting for wind and tide to take them to their next port. A ‘roadstead’ or ‘roadstay’ is a nautical term for a sheltered stretch of water, where it is (relatively) safe to anchor. In the Bristol Channel, hundreds of ships could be found anchored at Kings-road off Portishead, the Penarth roadstead, and other locations in the notoriously dangerous waterway. One sailing guide describes a roadstay near Ilfracombe, which was visited several times by Ashley on his lecture tours on behalf of the mission, in this way: ‘Ilfracombe is a little pier harbour, drying at low water; on its western point is a lighthouse… [O]utside of the pier there is a roadstead with good anchorage from 5 to 8 fathoms. This part is much frequented by coasting vessels; and pilots generally may be had here to conduct you to King’s-road.’ [J.W. Norie, New and Complete Sailing Directions for St George’s and Bristol Channels (London: Norie, 1816), p.1.]

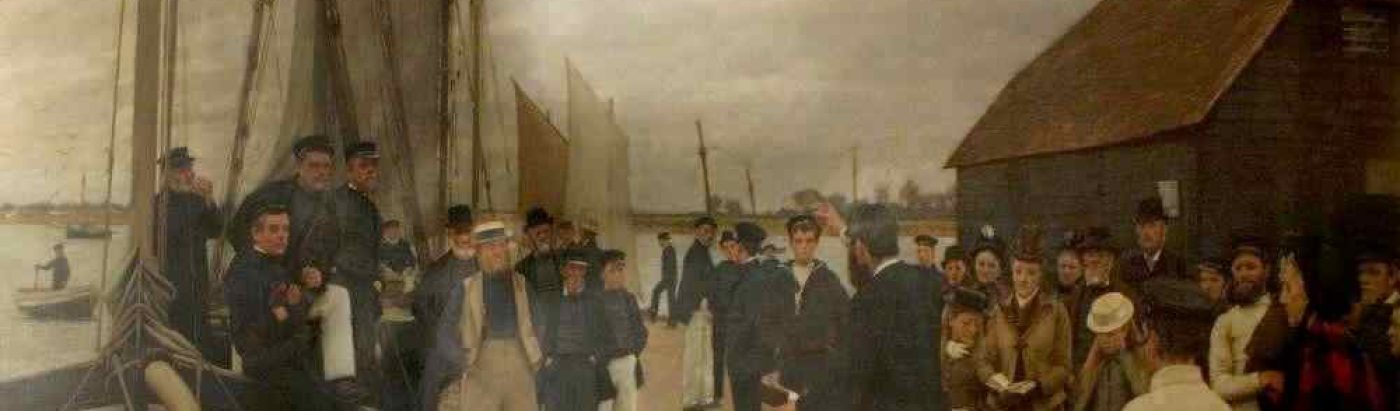

Although Ashley is usually said to have begun his ministry in 1839, it is necessary to rely on newspaper reports for much of the early history of the mission. According to the Bristol Mercury (one of 13 local newspapers serving the busy port city), Ashley was instrumental in creating the first roadstead mission and trying to reach seafarers afloat and at work. It was through his advocacy that funds were raised for a specially fitted vessel, the Eirene, which was built at Pill to Ashley’s specifications in 1841. The Eirene served not just to visit ships and distribute tracts, but also as a floating chapel. Along the busy roadsteads of the great Severn estuary, Ashley would preach, deliver sermons in aid of the mission, and advocate on behalf of the merchant seaman. Along the ports of the Bristol Channel, ‘it happened that considerable fleets of 200 to 300 sail were detained by contrary winds in Kings-road and the Penarth-roads’. [‘Bristol Channel Mission’, Bristol Mercury, 6 June 1840]. Most were commercial vessels, serving the coastal trade in goods such as coal, as well as imports from the Americas, sugar, tobacco, wine and spirits, meat, live cattle, fruit and timber. A lithograph in the Bristol Museums collection, dated 29 November 1843, shows the Mission Cutter Eirene, anchored among these vessels off Penarth, signalling that was time for divine service.

Ashley would later write about his mission in these terms:

Truly I pass from roadstead to roadstead here; as a dying man preaching to dying men. Every heavy gale that sweeps the sea buries in its abyss some of the Bibles I have sold, the books and tracts I have given, and in the prime and vigour of life, the men whose hands received them from mine. [‘Missions to Merchant Seamen‘, Churchman 4 ( 1881 ), 329.]

The Minute Book shows that Ashley and the BCMS had high-level support in the city, at least at first. The Society was formed ‘under the auspices of the Lord Bishop of Gloucester and Bristol [ie. James Henry Monk] for the purposes of sending a Clergyman to officiate among the fleets in Penarth-road, Kings-road, etc.’ [Taunton Courier, 22 Feb. 1842]. A sub-committee held at Sundon House, on 21 April 1843, was chaired by Charles Pinney (1793-1867), a Bristol merchant who had been Mayor of Bristol during the disastrous riots following the House of Lords’ rejection of the 1831 Reform Bill. Like the Ashley family and many wealthier Bristolians, Pinney is listed in the Legacies of Slavery database, and benefitted substantially from slave labour. Also on the BCMS committee was a future Mayor of Bristol, Thomas Porter Jose (1801-1875), a colliery owner and director of the Ashton Vale Iron Company, and George John Hadow (1789-1869), formerly of the Madras civil service and assistant under collector of sea customs. Hadow was an active philanthropist, and in 1838 also served on the committee of the Bristol Asylum for the Blind. Sundon House was Hadow’s Clifton home. At the second anniversary of the Society, the meetings was held in the Victoria Rooms, and was chaired by the then mayor of Bristol, James Gibbs. [Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian, 6 May 1843].

While Ashley was also on the committee, it is evident from the minutes that things were not all as they should be. For undisclosed reasons, Ashley demanded that the captain of the missionary cutter, the Eirene, be dismissed. While he was able to achieve his wish, it was not long before there was a parting of the ways.

As the Society’s debts mounted, Ashley and the Committee were on a collision course. Ashley failed to attend the Annual Meeting held in the Victoria Rooms on Thursday 25 April 1844. Money seems to have been the main issue. In June 1843, the Society decided to set the chaplain’s salary at £250 – backdated to 31 March 1843. Ashley seems to have declared war on the Committee, and began withholding subscriptions, including from the Merchant Venturers.

By December 1844, most of the Committee had had enough, and almost all of them resigned. This removed the treasurer, both Secretaries, W.C. Bernard and Jose, as well as the Committee’s leading cleric, the Archdeacon of Wells [Henry Law], along with seven clergy and seven laymen, including Charles Pinney. Ashley promptly offered to fill up all the vacancies with his own choice of officers, but – unsurprisingly – his offer was not accepted. At this rather exciting moment, the Minute Book ends.

There are press reports of accusations and counter accusations exchanged between Ashley and the Committee, though the pamphlets distributed by the warring parties have not survived. Perhaps this is just as well. In their reply to Ashley, the Committee quoted scripture: ‘He that is first in his own cause seemeth just; but his neighbour cometh and searcheth him.” – Proverbs 18, v. 17 [Bristol Times and Mirror, 5 Feb. 1845]

So what happened? The Society limped on, and Ashley himself went on an heroic fund-raising tour in 1852, moving from ‘town to town’ to support the cause. Ashley’s tour ended in London where, at a meeting chaired by Lord Shaftesbury, Ashley spoke for three hours on behalf of the mission he had founded. [Morning Chronicle, 11 June 1853]:

But it was not enough. In July 1856, the Bristol Channel Mission Society held its final meeting. There was a very poor attendance as the Committee explained that the Society would be wound up and incorporated into a new national organisation, based in London [Bristol Mercury, 5 July 1856]. With relief, it was also reported that the new Society would take over their debt of £450. This included all that was owed to Ashley, who had agreed to resign on being paid his full stipend of £400, an enormous salary by the standards of any other missionary society. By this stage, Ashley had already been replaced by three new chaplains, the Rev. T.C. Childs, well known for his mission to emigrants now extended to seamen from his base at Ryde on the Isle of Wight, for the English Channel, the Rev. C.D. Strong for the Bristol Channel, and the Rev. R. B. Howe for the Great Harbour of Malta. Putting on a brave show, the committee reported: ‘Feeling then that the time is come – that already the adequate discharge of our duty as a mission to the seafaring population of Great Britain is entirely beyond our strength as a small local committee, we propose that this society be now dissolved in favour of the society for promoting missions to seamen at home and abroad.’ [Bristol Mercury, 5 July 1856]

The Missions to Seamen (1856), incorporating both the Bristol Channel Mission Society and the Thames Church Mission Society (1844) was launched under new, more effective management. Ashley himself never recovered from the collapse of his vision, though fondly remembered as a pioneer of the Anglican Missions to Seafarers, and the first to attempt a direct mission to seafarers isolated on the roadsteads of the Bristol Channel. Based on the BCMS Minutes, the mission he pioneered succeeded despite rather than because of his involvement with the cause. However, given the many gaps in the record, it may not be possible to understand the full story.

Sources

Bristol Archives, 12168/18. Bristol Channel Mission, Minute Book, 1843-1844.

For accounts of the BCMS and the Rev. John Ashley: Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, Bristol Times and Mirror, Bristol Mercury, Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, Morning Chronicle (London), Southampton Herald.

Miller, R.H.W. Dr Ashley’s Pleasure Yacht: John Ashley, the Bristol Channel Mission and all that Followed. London: Lutterworth, 2017. [Available as an ebook here]

Miller, R.H.W. ‘Thomas Cave Childs: Pioneer chaplain to female emigrants and the Missions to Seamen’, The Mariner’s Mirror 106.4 (2020), 436-449.

For older views of Ashley:

Strong, L.A.G. Flying Angel: The Story of Missions to Seamen. London: Methuen, 1956

Walrond, Mary L. Launching out into the deep; or the pioners of a noble effort. London: SPCK, 1904.